What sparked the protests, and where they spread

One court ruling lit a fuse. On August 19, a judge sided with Epping Forest District Council in its effort to close a hotel housing asylum seekers on planning grounds. Within days, anti-immigration activists seized on the decision and called fresh protests outside hotels across England. By the August 23–25 weekend, rallies had appeared in Bristol, Leicester, Newcastle, Liverpool, and Horley, with smaller gatherings reported in several other towns.

These protests targeted the government’s widespread use of hotels as temporary accommodation. Around 200 hotels currently house about 32,000 people whose claims have not yet been resolved. The sites became focal points after the Epping ruling because campaigners viewed it as a template: if one council could persuade a judge to force a shutdown, perhaps others could too.

Most of the weekend’s demonstrations were non-violent, but the mood was sharp. Chants and banners carried a hard anti-migrant message, and in many places antiracist counter-protesters were outnumbered. Police stood between groups to reduce flashpoints and keep entrances clear for residents and staff.

Horley, Surrey, saw one of the largest crowds on Saturday, outside the Four Points by Sheraton. Roughly 200 anti-migrant protesters lined the road, while about 30 members of Stand Up to Racism held a counter-protest near the train station under police protection. The gatherings drew extra attention because ReformUK, which now leads national polls by around 10 points over Labour, amplified the event and framed it as a test of local resolve.

In east London on Sunday, uniformed officers kept watch at the Britannia Hotel near Canary Wharf. Protesters waved union flags and hoisted homemade signs, including one referencing Tower Hamlets’ council housing list. The crowd ranged from adults wearing Tommy Robinson supporter shirts to school-aged attendees wrapped in the flag. Police later confirmed arrests at different sites over the week, and officers reported injuries in earlier protests tied to the same dispute in Epping.

The link to last summer’s unrest hung over the weekend even as events largely stayed calm. In August 2024, racist riots flared after the Southport killings; those scenes still shape how police prepare for public order risks today. Forces increased staffing around key hotels, put barriers in place at entrances, and directed traffic away from the biggest bottlenecks.

Unlike 2024’s violence, this wave was about pressure—on councils, courts, and the Home Office. Activists want more councils to challenge hotel use through planning law. Supporters of asylum seekers fear that success in one courtroom could push others to displace vulnerable people with very little notice. That tension framed every chant and every police cordon across the weekend.

The legal fight, the politics, and what comes next

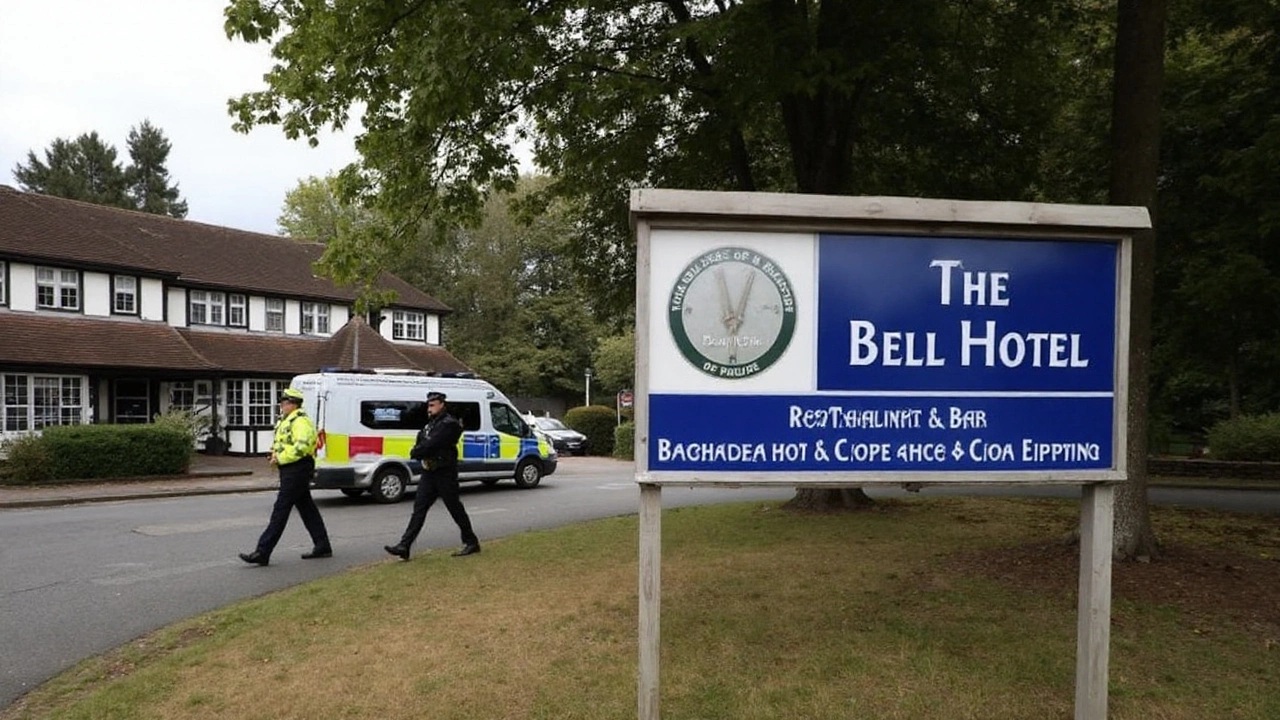

The legal front moved quickly. On Tuesday, the High Court granted Epping Forest District Council a temporary injunction requiring asylum seekers to leave the Bell Hotel in Epping, Essex, by September 12. The Home Office said it would appeal. While this is a single case, it is already shaping strategy elsewhere: several councils are studying similar actions, and campaigners are openly sharing playbooks on how to challenge sites on planning grounds.

Why planning law? Councils argue that long-term use of hotels as accommodation for asylum seekers amounts to a change of use that needs permission. Some say hotel conversions strain local services and fall outside agreed local plans for housing and community support. The Home Office, facing pressure to cut costs and backlogs, has kept using hotels as a stopgap while it tries to move people through the system more quickly.

That clash—between national policy and local control—sits at the center of the Epping case. If the Home Office loses on appeal, the ruling could encourage a patchwork of local injunctions, forcing faster closures and relocations. If the Home Office wins, it would strengthen its hand to keep hotels open while claims are processed. Either outcome will affect thousands of people and the councils hosting them.

Politics is pulling hard on the same threads. ReformUK used the Horley demonstration to push its national message and capitalize on anger about migration and housing shortages. With a single-digit lead in some polls, ReformUK’s presence at protests gives the gatherings a louder megaphone—and turns local planning rows into national talking points. That puts pressure on both the government and Labour-run councils, which are caught between legal risk, budget limits, and local voter concerns.

Ministers say they will overhaul the asylum appeals system to speed decisions and reduce hotel use. That speaks to the immediate complaint many residents raise: the length of time people stay in limbo. But it won’t resolve the question of where people go right now. Any policy shift will take months to roll out, and the current hotel network is still carrying the load.

Inside the hotels, daily life is basic and controlled. Residents typically receive meals, security checks, and curfews of varying strictness, depending on the site. For staff, the protests bring extra stress: more ID checks, limited access for deliveries, and frequent police presence at entrances. Local volunteers still try to deliver clothes, books, and language support, but they sometimes face protesters at the gate. Councils have started adding barriers and extra guards after scuffles at several sites earlier in the week.

Counter-protest groups, including Stand Up to Racism, focused on visible solidarity. They positioned themselves near transport hubs or across the street to avoid direct clashes, and they coordinated with police to keep routes open for families. Their turnout was smaller in many towns over the weekend, but they plan more organized responses if councils move to evict residents before appeals are resolved.

For hotels, another practical issue looms. Operators face legal uncertainty and reputational risk. A council injunction can force rapid changes to contracts, staffing, and bookings. Even if a hotel is ultimately allowed to continue, weeks of demonstrations can depress business and rattle suppliers. Some chains have already begun to review their portfolios to limit exposure to sites that could become flashpoints.

The financial backdrop is not subtle. Housing people in hotels is expensive, and every week of delay adds to the bill. Councils say the setup strains local services and police budgets, while charities warn that abrupt moves out of hotels—especially for families and those with medical needs—can cause real harm. Many groups want a shift to stable housing and faster casework rather than headline-grabbing relocations that simply move the problem to a new postcode.

Meanwhile, the map of protest activity is widening. Beyond Horley and Canary Wharf, Bristol saw crowds outside a central hotel, while Leicester and Newcastle dealt with rolling gatherings that shifted locations as police set up cordons. In Liverpool, activists chose a site near a busy junction to maximize visibility. Turnout varied, but the pattern was the same: banners at the front, police in the middle, and counter-protesters set back from the entrance. In several places, residents were escorted in and out through side doors to avoid confrontation.

The slog ahead is legal, political, and human all at once. The Home Office is racing to appeal the Epping injunction and avoid a chain reaction. Councils are weighing the costs of court action versus the risk of doing nothing. Activists on both sides are planning more weekends on the pavement. And thousands of people waiting for asylum decisions are caught in the middle—unsure if they will be moved again, and when.

In practical terms, the next checkpoints are already set. The Epping order takes effect on September 12 unless a higher court pauses it. Other councils will likely file similar claims in the coming days, testing how far planning law can stretch. Police forces will keep public order units on standby around hotel sites and transport hubs. Hotel operators will push for clearer guidance from central government to avoid last-minute cancellations and rushed transfers.

This comes as national debate hardens. ReformUK is pressing its poll advantage with promises of stricter controls. Labour and the government face pressure to show faster asylum decisions and fewer people in hotels. And local leaders want the power—and the funding—to manage whatever policy lands in their lap. With no quick fix in sight, the United Kingdom is set for more weekends like this one: loud streets, heavy police tape, and the same unresolved question about who decides where people live while they wait.

At the center of it all is one simple fact: the network of asylum seeker hotels has become a stand-in for a much bigger fight. It’s not just about a single building or a single council. It’s about who sets the rules, how fast the system moves, and whether communities feel listened to as pressures mount. As the legal appeals begin and the next round of protests forms, those are the lines that will decide what happens next.