He was called a saint. He left England on the brink of conquest. The new biography under review by medievalist Tom Shippey tries to square that circle, peeling back the glow to show the wary operator beneath the halo. It argues that Edward the Confessor was not a timid passenger in his own reign, but a survivor who learned to read people, stage-manage power, and keep a lid on crisis—until the one decision that mattered most slipped through his fingers.

A king shaped by exile and the Godwins

Start with the childhood. Edward spent years in Norman exile while England swung between competing rulers. That long watch from the sidelines—always listening, rarely speaking—taught him the value of timing and the danger of making enemies you can’t crush. When he finally took the throne in 1042, he moved with care. He brought in trusted Normans but he also needed the biggest English power bloc: Earl Godwin of Wessex and his fast-rising sons.

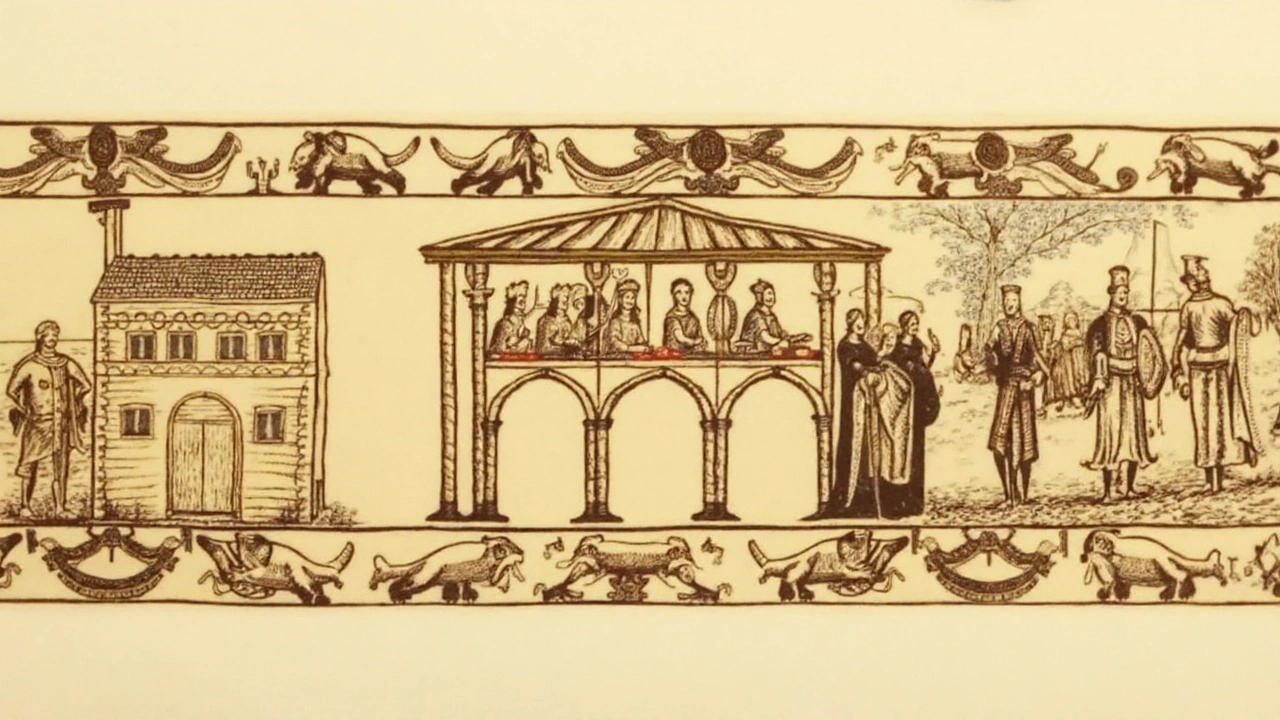

His marriage in 1045 to Edith, Godwin’s daughter, tied the court to that family. It was a political match, not a romantic one, and it had a clear upside: the Godwins delivered muscle and money. The downside? They were a dynasty within a dynasty. By the early 1050s, they controlled most of the map. Harold Godwinson dominated the south and east, Tostig later took the north, and other brothers dotted the midlands and coast. Everyone could see where the wind was blowing.

The flashpoint came in 1051. After a brawl in Dover, Edward ordered Godwin to punish his own power base. Godwin refused. The king called in help from the midlands and the north, and both sides assembled armed men. This could have spiraled into civil war. According to the biography, it didn’t—because the ordinary soldiers balked. Many weren’t willing to fight neighbors over what looked like a feud among the elite. The stand-off ended with Godwin’s exile, not a battlefield. That matters. It shows a king who could step back from the brink and accept a political exit rather than force a bloody win he might later regret.

Edward’s power often came wrapped in courtesy. Shippey highlights a small moment that captures this: Queen Edith lost her temper when a visiting French abbot refused her the kiss of peace. It could have turned ugly. Edward softened the blow with a neat line—holy abbots, he said, keep strict vows and avoid all contact with women, unlike the more relaxed English. Everyone saved face, nobody lost status, and the court moved on. It’s a tiny scene, but it shows how he defused anger without publicly humiliating allies.

That style shaped his message to the Godwins. The book leans on a sharp metaphor: a man who keeps wolves doesn’t fear being bitten—or he’s too afraid to drive them off. Edward kept the Godwin clan in the room, in office, in his orbit. He also balanced them with rivals when he could, leaning at times on the earls of Mercia and Northumbria. Often his “statements” were not speeches but appointments, charters, seating plans, and building projects—signals everyone at court could read. Westminster Abbey, which he rebuilt on a new scale, did double duty: it burnished his sacred image and anchored a royal center of gravity just outside the City of London.

But keeping wolves is risky. In 1052 Godwin came back from exile with ships and support, and the king had to take him and his sons back into favor. Harold’s star rose higher. Tostig later took Northumbria, where his rule turned harsh. In 1065, the north revolted, and the court threw Tostig out rather than start another national crisis. Edward looked less like a king in command and more like a referee trying to prevent the league from collapsing. He was still good at avoiding bloodshed. He was no longer good at making the big calls stick.

The succession that broke England

What does a medieval king owe his people? Strip it to basics and you get three tasks:

- Hold the realm together and keep the peace.

- Protect the church and sustain the crown’s legitimacy.

- Deliver a clear, stable succession.

Edward managed the first two, more or less. England wasn’t free of tension, but the realm didn’t tear itself apart on his watch, and his alliance with the church—capped by Westminster—shored up the monarchy’s image. The third task undid everything.

The problem was simple and brutal: he had no children. With no obvious adult heir, every move he made was read as a signal. In 1057 he tried to solve it by recalling his nephew, Edward the Exile, son of Edmund Ironside, from the far edge of the family’s wanderings. The backstory shows the churn of the age. The exiled branch had drifted through Scandinavia and the courts of Kievan Rus before settling in Hungary. They were safe, but far from any English power base. When Edward the Exile finally returned, he died soon after setting foot in England. His son, Edgar the Ætheling, did not die—he survived—but he was young and, crucially, came with no army, no landed faction, and little leverage at court.

From that point, the signals grew messy. Did Edward favor Harold Godwinson, the man who kept the government ticking and knew every earl and sheriff in the land? Or did he lean toward his Norman kin? Later Norman sources claimed the king had already named Duke William as heir, and they point to Harold’s fateful trip to Normandy in 1064 and the oath he reportedly swore there. English accounts push back. What’s undeniable is the ambiguity. By trying to balance factions and avoid an explosion in his lifetime, Edward sent mixed messages about what should happen after it.

The Tostig crisis made it worse. When Northumbria rebelled in 1065, the court ditched Tostig to keep the peace. Harold gained yet more influence. The king, ill and aging, seemed to recede. When he died in January 1066, the Witan—the council of leading men—chose Harold as king. That choice reflected the political map as it stood inside England. It did nothing to stop claimants outside England from pressing what they believed they had been promised.

We know what came next: two invasions within weeks, first by Harald Hardrada from Norway and then by William of Normandy. The campaigns of 1066 turned Edward’s long effort to avoid civil war into something worse—a year of two great battles and a new ruling class.

So why did a careful manager fail at the one decision that mattered most? Part of the answer is structural. The rules around succession in Anglo-Saxon England were flexible. Kings were “chosen” from the royal blood, usually the strongest viable candidate with the Witan’s support. That made politics in the here-and-now matter more than abstract rules. Without an adult ætheling to rally around, everyone read the tea leaves differently—and acted on their own interests.

Another part is personal. Edward’s strengths were day-to-day: patient diplomacy, symbolic gestures, and a knack for letting adversaries back down without losing face. Those are not the same skills you need to ram through a succession plan all sides will accept, especially when that plan cuts across the interests of the sons of the most powerful earl in England. The wolves he kept at court were loyal to England as they saw it—and to themselves. Trusting them to accept a settlement that sidelined them was a gamble he would not, or could not, force.

The saintly image that later grew around Edward hides that harder truth. He was canonized long after his death, and the cult centered on Westminster turned him into a model of royal piety. There’s no need to deny his faith to see the politics underneath. He used religion to strengthen the crown’s aura. He used his building program to root the monarchy in stone. He used courtesy to disarm rivals. None of that answers the succession question when the kingdom’s most potent family can deliver the crown’s daily business and the army to back it.

This is where Shippey’s review lands its punch. Edward wasn’t the soft touch of old caricatures, nor the flawless patron-saint of tidy legend. He was a wary, skilled operator who kept a country of strongmen in balance for nearly a quarter century. He was also a king who misjudged how fast that balance would snap the moment he was gone. The message he thought he was sending—orderly transition, sacred monarchy—was heard in different ways by Harold, by William, and by every armed retainer from Dover to York. And once those messages clashed, the peace he had protected for years couldn’t survive a single winter without him.